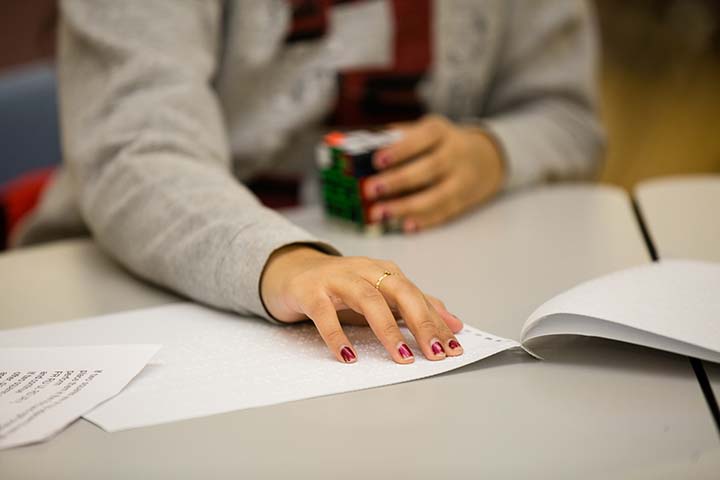

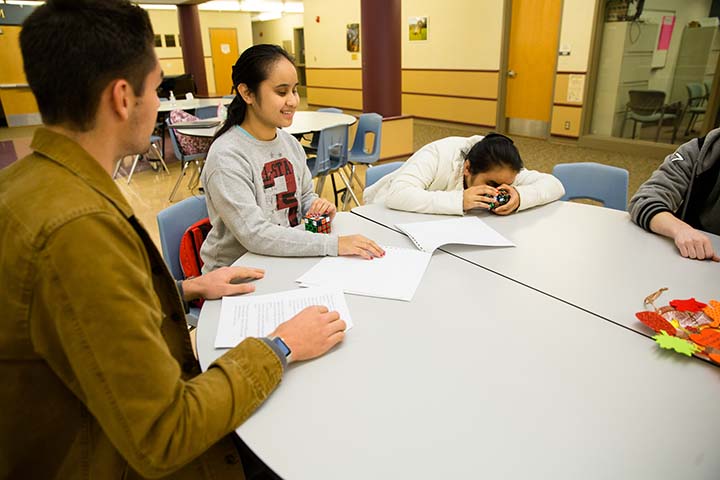

First photo: Fenix Roark examines the tactile cube. Second photo, from left: Oryann Fitim, Carson Mowrer, Sasha Thomas, Sioryann Fitim and Fenix Roark. Third photo: Oryann Fitim reads cubing instructions. Fourth photo: Mowrer, Oryann Fitim and Sioryann Fitim. Fifth photo, from left: Fenix Roark and Sasha Thomas work on a cube. Photos by Cheryl Boatman.

“If you are curious, you’ll find the puzzles around you. If you are determined, you will solve them.” —Erno Rubik, creator of the Rubik’s Cube

Tactile Rubik’s Cube puts twist on favorite pastime

The brightly colored square that could be found in the hands of nearly every child of the ’80s has yielded countless hours of both fun and frustration. The Rubik’s Cube is said to be the all-time best-selling toy, reaching approximately one in seven people according to its official website.

But what if you couldn’t see? No cubing for you, right?

Not necessarily.

Sasha Thomas, a senior at Vancouver iTech Preparatory, and Carson Mowrer, a senior at Skyview High School, want to bring the pastime to people with visual impairments.

Working outside of school time, Thomas and Mowrer brought an engineering perspective to their cube. “When solving a Rubik’s Cube, you need to be aware of the colors that are opposite of each other,” said Thomas. “For example, you need to know that white is opposite of yellow. However, visually impaired students don’t know that, so we tried to come up with a way that they could easily recognize that.”

Their solution: adhere textures to the surface of each smaller cube, or cubie. Velcro, small raised foam dots, hard plastic pieces and other textures all stand in for colors on Mowrer and Thomas’ 3 x 3 tactile cube, which they hope eventually to patent and bring to more people with visual impairments.

Students from the Washington State School for the Blind provided valuable insights into distinguishing textures. “By using their feedback, we can create a puzzle that works the best for them,” said Mowrer, a student in Skyview’s Science, Math and Technology magnet program.

Cubing has been a hobby for Thomas and Mowrer since seventh grade, with Mowrer even solving cubes competitively. But Thomas’ father’s work with blind veterans provoked them to think about how to make the experience more inclusive. “We can share this hobby of ours that we’ve been involved in for several years with a segment of the community that’s been isolated from it,” Mowrer said.

Oryann Fitim solves a tactile cube.

“It twisted my brain really good,” said Oryann Fitim, a senior at the School for the Blind, of the first time she attempted the tactile cube. But she was intrigued. “If I can solve at least one layer, I think any visually impaired student can,” said Fitim.

Cube founder Erno Rubik needed one month to solve his first cube, according to the toy’s website. Fitim solved not only one layer, but the entire tactile cube on just her second encounter, joining the ranks of successful Cubers.

Perhaps just as important, she found a new way to connect with those closest to her.

“When I got to bring mine home, I showed it to my parents and my family,” said Fitim. “Whenever they have Rubik’s Cubes, I always hear swish, swish, swish. I went home and was like, ‘I get to join you guys! I’m a part of you guys; I have one too!’ ”